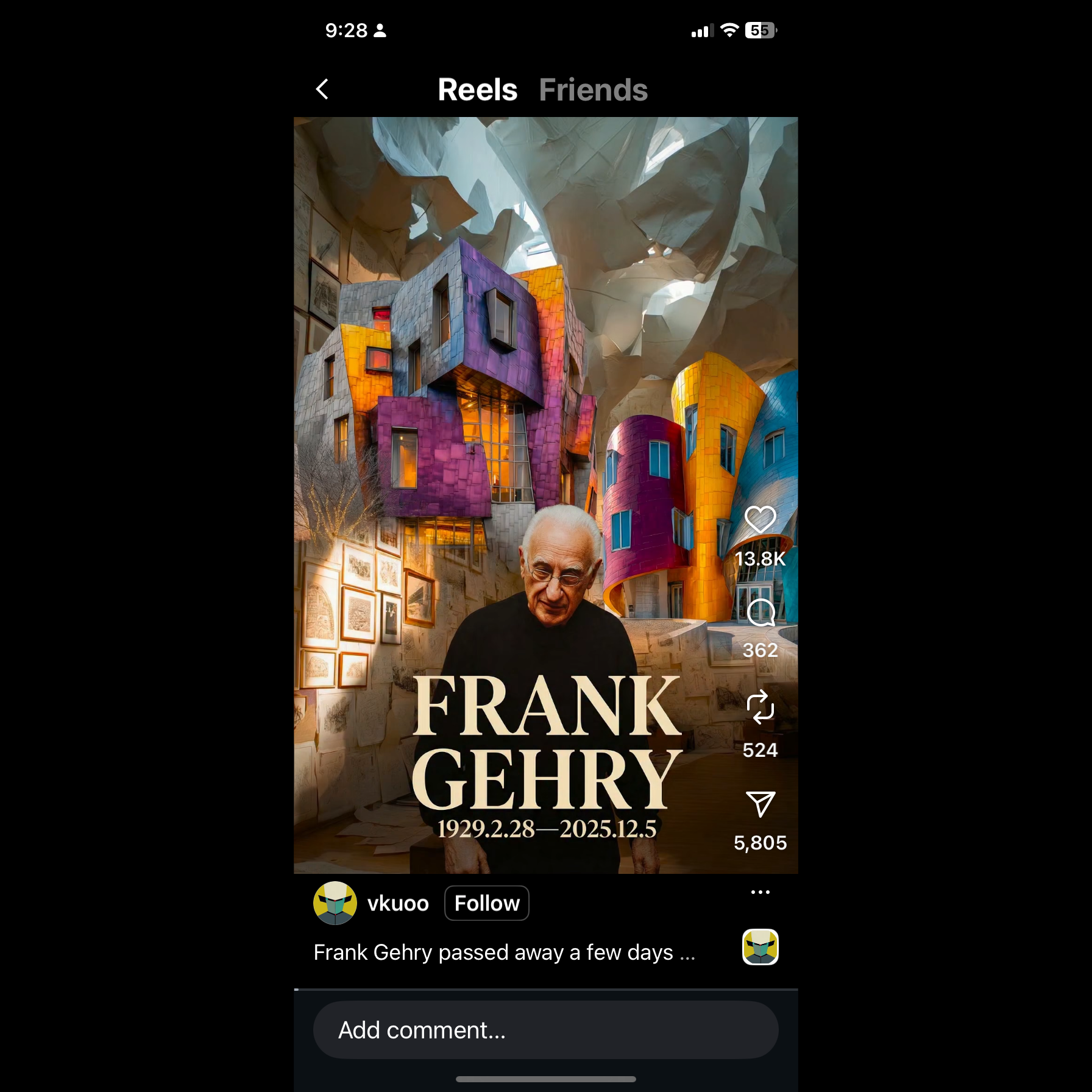

“I don’t think the building has to be that antagonist to the art.” — Frank Gehry

It is shocking to learned that one of our respected architects, Frank Gehry, passed away last week. While reading the flooded news and stories in remembrance of this star architect, it reminded me of one of his opinions about art and architecture: "Artists have trouble with scale in the city because the city is such a large scale. No one ever commissions artists to make sixty-story sculptures, and until one of them makes a sixty-story sculpture, their works will not stand beside the Empire State Building and mean anything."

So, how do we "literally" and "metaphorically" link our buildings and cities so that the structure before us is no longer merely a "building" but an "architecture"? I cannot stop asking myself this question.

If we take a bird's-eye view of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, we would see the shape of a blooming Big Dipper. That shape was reflected from Bilbao's old town district (Casco Viejo), which was centered around its core: Cathedral Basilica of Saint James (Spanish: Basílica Catedral de Santiago; Basque: Donejakue Katedrala). Though nowadays the boundary of the old town has already blurred and been revised to current administrative needs, we can still tell the big dipper shape by reading its urban fabric-- with the cathedral as the center location of the bloom. The metro line cut through the park (Areatzako Parkea), which also reflects on the relationship of the lower profile of the museum: the "boat gallery"(Arcelor Mittal Room), and its flyover bridge (Puente de la Salve).

And how about the Nationale-Nederlanden Building (also known as the Dancing House/Ginger and Fre) in Prague, you might be curious.

Everyone knows that the building looks like a couple dancing. But why does he choose a dancing couple, not another kind of protagonists, maybe a general horse, which we often see at a roundabout?

The first Prague model had two square towers: one projected out, the other stood straight. Gehry blended them, carved the curvature, and made one tower clad in glass panels. Then the model looks like a dressed woman with translucent and feminine contours.

Programmatically, the translucent and opaque towers make sense: the opaque tower with punch windows was for hotel guest suites, and the glassy part contains restaurants, cafes, and conference rooms. The cylindrical shape and the dancer's flying-skirt canopies also helped the developer gain additional square footage. Yet, compared to its historic landmark neighbor (Pamětní deska), Gehry's new proposal seems to undermine European's intellectual, not to mention their then-poetic president, Václav Havel.

The designer and client might have gone through many conversations behind the scenes that were not recorded. But this curved building's avant-garde gesture makes sense given how it is located. If we take a close look at the two bridge abutments, we can tell they are distinctly different: the one in the old district (west) has a sharp pyramid-shaped roof profile. The one at the new town district (east) has a curved, onion-shaped roof profile. Presumably, the difference is for boat travelers to see better "signs" and distinguish which direction they are heading.

Gahry's new dancing house on the east side of the river enhanced these abutments' original wayfinding purpose and proudly announces the new town's significance in history.

Yesterday, I just read about the significant policy shift by the US Department of Education that architecture is no longer a "professional degree". The news reminded me of my old-time question of "art and architecture". Everyone can be an artist, yet the approach to architecture should be like science, not the repetition of old ideas. Whether Gehry's Dancing House at a crucial corner along the Vltava River or his blooming museum debuted beside the Nervion River. Each of his sketches involved budget calculations and neighborhood contextualization.

By the way, when talking aboout budget calculation, this is what really happened to the projects…

The Dutch insurance company National-Nederlanden (ING Bank 1991-2016) agrees to sponsor the construction onsite. Because of the bank's excellent financial state at the time, it was able to offer unlimited funding for Gahry's project. Compared to the Dancing House, the Guggenheim Museum at Bilbao was set up with tough budget calculations. It is easy to budget a ship from $300 to $400 a square foot. Yet the titanium cladding surface was approximately two feet by three feet, and the joint is a traditional locked seam. So the design team has to use CATIA software to calculate the surface area for the material.

If you are interested in this topic, you might also like:

Notes and references:

Mildred Friedman, editor, Gehry Talks: Archuchitecture + Process, (Universe Publishing, 2002)

Dancing House, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dancing_House#cite_note-4, Acessed 9, December 2025.